A new story in the Mongolian Wizard universe.

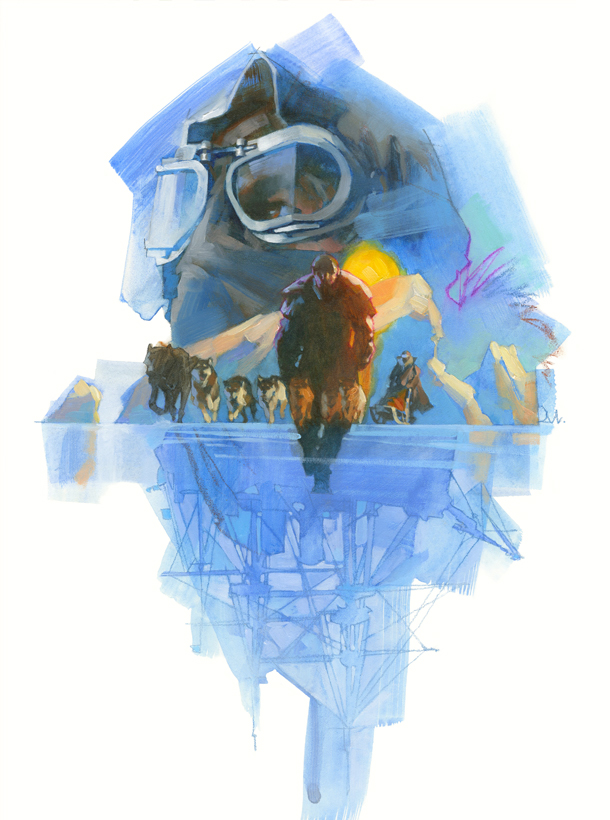

The Arctic wastes stretched wide in every direction, vast and irregular plains of ice which seemed to have no end. At their center, barely visible in the weak light provided by a sliver of sun at the horizon, was a rapidly moving sled. It was pulled by eight dogs with a single wolf at their lead, and ridden by a large man bundled in Sami furs.

Ritter welcomed the cold and hardship as an opportunity to test his manhood against Nature at its harshest. The scarf wrapped about his lower face was stiff with ice frozen from the moisture of his exhalations and what little of his skin was exposed to the air felt numb. When he bit off a mitten and pressed a hand over his eyebrows, the flesh beneath was warmed to life again and began to sting. The air was still and that, he had to admit, was good for it allowed Freki to follow the scent of their prey with ease.

He had pursued the half-man from Europe and was prepared to pursue him to the Pole if necessary. He was sure it would not be, however, for the traces of the homunculus’s passage had not been erased from the snows. Ritter was close on his trail.

A nub appeared on the horizon.

Ritter drew up the sled and, taking out a pair of binoculars superior to anything he could have imagined a year ago, studied the anomaly. Under magnification, it revealed itself to be a canvas tent that had been insulated by stacking up blocks of snow on all sides and piling more loose snow over its top.

Methodically, Ritter disentangled the sled dogs from the harness. Then he gave them a mental push to trot back a mile or so the way they had come and wait for him. If he died, his hold over the dogs would cease and then they must do their best to survive on their own. Ritter was not sure that they could. But at least they would have a chance.

He heaped snow over the sled, so that it looked like any other unimportant lump of landscape, then lay down behind it where he could not be seen. He was far from convinced such precautions were necessary. But he had underestimated the creature’s abilities in Helsinki and would not do so again.

Then he sent Freki ahead to serve as his ambassador.

The wolf loped across the snow and, upon reaching the tent, scrabbled at the canvas door. Then, when hands from within pushed it open, he rolled over on his back, exposing his stomach.

The homunculus looked down on the wolf and smiled. Kneeling, he stroked the animal’s underside and scratched it behind one ear. So far as Ritter could tell, he did not project his consciousness into Freki’s mind for even an instant. Nevertheless, the creature said aloud, “You are a diplomatic fellow, whoever you are. Come and talk to me. I promise no harm will come to you.”

Ritter stood, brushing off snow, and began the long trudge toward the tent.

Buy the Book

The New Prometheus

“The safest thing would be to kill him on sight,” Sir Toby had said. He and Ritter were in his London office, a walnut-paneled room frowsty with cigar smoke and casual treachery.

“I am no assassin. If murder is your intent, send a professional.”

“So I did, three of them. This is no ordinary man. Indeed, by most accounts, he is hardly a man at all.”

In Ritter’s experience, when his superior emphasized the inhuman nature of an opponent, whether physical, mental, or moral, he intended actions such as no decent man would visit on a fellow member of human society. Scowling, he said, “How do you mean?”

“He is a homunculus—an artificial man. There were reports—as reliable as such things can ever be—that the Mongolian Wizard had created a being with powers exceeding even his own. You will read them on your way to Helsinki. He is reputedly of great stature, inhumanly strong, and capable of wielding every known form of magic. For reasons yet unknown, this prodigy broke free of his creator and fled westward. There were several desperate attempts to recapture him. That caught our interest. Then his pursuers simply turned around and went home. Which by itself convinced me that such a being is too dangerous to be allowed loose in the world. While on the run, he somehow managed to acquire a great deal of wealth. Currently, he is using it to provision a ship. A schooner awaits you at the docks. If you leave immediately, you can intercept him before he departs for wherever he is bound.” Sir Toby fell silent. After a long pause, he said irritably, “Why are you still here?”

“I’m not sure I understand what you expect of me.”

“Use your own judgment. You have a certain…flexibility in these matters.”

Ritter had never before been accused of flexibility. He decided to receive the declaration as praise. Nevertheless, he said, “If I must kill him, I will. However, I require full autonomy in this affair. It is entirely possible I will end up letting this fellow remain alive and at large.”

Sir Toby sighed. “So be it.”

“I am prepared to offer you asylum,” Ritter said, “in exchange for what you know about the Mongolian Wizard. You will be given a modest stipend for as long as you need it, an apartment of your own, assistance in finding work, a new identity. By this time next year, you will be a citizen of London like any other.”

The homunculus laughed. “A grotesque like me?”

“You are a little tall, perhaps. But not beyond the range of human possibility.”

“It was you who shot at me at the docks, wasn’t it?”

“I had no choice. You rebuffed my invitation to parlay and the ship was pulling out.” Watching the man’s eyes and seeing in them no trace of intemperance, Ritter decided to take a chance. “I hit you too. You grimaced, clutched your chest, and bent over. I am certain that I saw blood. But when you straightened again, it was gone.”

“You hit my heart, yes. Any other man would have died then and there. But I did not. Would you like me to tell you why?”

“It is my most fervent hope that you will.”

“I was born by immaculate conception.” The homunculus was a handsome fellow, though his extreme height—he was a good eight feet tall—rendered even that alarming. He had given Ritter a barrel of salt pork for a chair and himself sat cross-legged on his sleeping pallet, putting their eyes on the same level. “Do you know how that works?”

“I am afraid that I do not.”

“It is a gruesome process. First the skeleton is assembled from the living bones of various animals. Human bones would not do, for it was desired to give me the features and physiognomy of a god. Bones taken from dead creatures would be…dead. So animals were required to suffer. It took a phalanx of surgical wizards just to keep the skeleton viable while muscles and cartilage were attached, nerves grown to interlace the flesh, organs coaxed into interaction, skin convinced to cover all…More magical talents were employed in my creation than for any other single purpose in human history. It is doubtful that anyone but my father—for so I consider him—could have arranged for such a thing. And even he had to effectively bring the war to a standstill to free up the resources necessary for it.”

“I’m sorry—which war was this?”

“The current one. Difficult though this may be for you to believe, I was created barely six months ago.” The homunculus proceeded to tell his tale.

My earliest memories are of combat. Day after day, I was drilled to exhaustion in all the martial arts. My father I never saw. His place was taken by a weapons master, a pompous but capable Austrian named Netzke who taught me to fight with dagger, sword, pistol, rifle, and singlestick. Specialists were brought in to train me in fisticuffs and various other forms of bare-handed combat. Herr Waffenmeister Netzke worked me hard. At the time, I had the understanding of a child for I was mere weeks old, and it did not occur to me that I had any choice but to obey him.

At night, as I was falling asleep, I heard voices. At first, they were a soft murmuring, as of a not very distant sea. But day by day they grew louder and more insistent, as if they were saying something I needed to know but could not understand.

When I asked Netzke about the sounds and what they meant, instead of raising his fist to strike me as I’d more than half expected, he looked thoughtful. “They mean we must accelerate your training,” he said, and the very next day he brought in a wizard to tutor me in pyrokinetics—a much more likable fellow than Netzke by far, the Margrave von und zu Venusberg.

A harsh cry involuntarily escaped Ritter’s lips.

“I’m sorry, is the margrave someone you knew?”

“He is my uncle. A most excellent man and one who disappeared when Bavaria was overrun. I can scarce believe he would betray his own country. I…No, pray continue. Forgive me for interrupting.”

The homunculus placed a hand on Ritter’s shoulder. “He would not have had any say in the matter. The Mongolian Wizard has ways of converting talented people to his cause. But allow me to return to my story and, though it is not a happy one, perhaps you will find some small measure of comfort in it.”

It was the margrave who convinced Netzke that I was being overworked. “You are like the swordsmith who heats his creation red hot,” he said, “and then quenches it in oil, only to return it to the furnace again, back and forth, over and over, until the metal is so brittle it will break with the first blow struck in battle. Your charge has a brain—he must learn to use it as well as his brawn.”

Hearing the logic of those words, Netzke agreed, though reluctantly. So the margrave set out to teach me how to read. After the first hour of his ministrations, I grew impatient. “Explain to me the principles of this skill,” I demanded. And when he had done so, I astonished him by picking up the text he was using as an exemplar, Caesar’s Commentaries on the Gallic War, and reading the first several pages aloud.

Thus, I gained access to my father’s library.

I was in Heaven. In short order, I read Milton’s Paradise Lost, Plutarch’s Lives, and, most sublime of all, The Sorrows of Young Werther. From there, I went on to Rousseau and Kant and Locke and Descartes and Spinoza and Hobbes and, oh, so many more! I entered the library little more than an animal. Reading books made me human.

Perhaps it was coincidence, perhaps not. That evening something broke open within me. I realized that the sounds I heard were words, though neither spoken nor written. I was eavesdropping on the private thoughts of those around me: their fears, greeds, lusts, hatreds…It was not a pleasant experience. Much of this, I have since learned, came from my being in a nexus of worldly power, which necessarily drew to it, like flies to rotting meat, the worst exemplars of humankind. But even in the best of men there are dark thoughts and unwelcome fantasies. Had I lived in a monastery, the minds of the holy brothers would have been a torment to endure. And, having mastered literacy, my weapons training began anew. Only now, understanding—or so I thought—their intent, the exercises were repugnant to me.

At such a miserable time, your uncle was a godsend. In me, I think, he saw the mirror of his own unhappiness. We both despised our situations yet could see no way free of them. Young though I was, he spoke to me as if I were his equal, freely sharing his doubts and regrets. He was, as I am sure you know, a good man. From him I learned that to be human was not necessarily to be evil.

“Sir?” I asked him once. “Why is the world in books so much better than the world in life?”

After a long, thoughtful silence, the margrave replied, “People often relate arguments they have had and claim to have said things they only thought of later. Novels are life lived as it should have been and factual works such as essays and history are thought laid out without the false starts, blind alleys, and easy assumptions we experience in the event. That’s all.”

“I intend to think clearly the first time, and to live life without making mistakes.”

It was a callow thing to say, but the margrave only replied, “Well, perhaps you will be the first man to manage that trick. In any event, I encourage you to try.”

The margrave also taught me the rudiments of projecting fire with one’s thought, a skill I have since expanded far beyond anything he could ever have envisaged. As with reading, this skill opened new worlds to me. All forms of magic are but expressions of a single talent—I see you nodding, as if you had already suspected as much—limited only by the mental capacity of its possessor. Most people can wield this talent not at all. An elite class can, with training, master a single skill toward which they have a predisposition. And scattered here and there are a handful of extraordinary individuals who can master two or even three skills without being destroyed by them.

There are many such skills. In short order, I became the master of them all.

Word of my accomplishments spread swiftly through the court. We were housed in an ancient castle near the Russian border—by your expression, you know which one—whose windows had been bricked up and courtyards covered over to prevent men like yourself sending goshawks or the like to eavesdrop upon us. Though I more than once fancied I heard faint thoughts emanating from behind the wainscoting, which suggested you had spies diminutive enough to ride mice through small openings in the masonry. Be that as it may, the castle was a dark place.

So it was in a gloomy chamber insufficiently lit by whale-oil lamps that Netzke showed me off before a crowd of high-ranking officials. “This is our big day, eh?” he said, rubbing his hands together. Then he ran me through my paces. I bent iron at a distance, levitated, ran a dagger through my hand and then closed and healed the resulting wound, and made a dead rabbit hop and then, rising up on two legs, dance a gavotte. Finally, for the climax, Netzke commanded me to destroy a dummy tied to a cross at the far side of the room. Nothing could have been simpler. With a thought, I turned it to ashes—and burnt off the eyebrows of those who stood too close to the dummy, to boot.

The crowd broke into spontaneous applause. They were all smiles.

But I could read their dark, ambitious thoughts.

The Mongolian Wizard—even in his own court, he had no other name—was away on business of the Empire. But now Netzke announced that, my education being complete, he would be sent for and that within a fortnight, I would meet my father at last.

More applause.

I told you that animals had to be cruelly abused to create my frame. Only one animal could donate the materials that make up my four-lobed brain—the human animal. I had known this fact from very early on. My readings then made me aware of how vile a deed this was and, as a result, I was profoundly ashamed of my origins. Nevertheless, having more to think with than other mortals, and it more efficiently structured, I could perform prodigies of reasoning unknown to lesser men. All in a flash, I realized that my father had not had me created as a weapon, as I had previously assumed, but as a host for his identity. Using his own uncanny powers, he would oust me from my brain and assume my body as an ordinary man might don a new coat. The first such, moreover, of many he would assume in a lifetime that might well last a thousand years.

I stood transfixed with horror.

It was the worst of all possible times for Netzke to nudge me in the ribs and say, “You will sit at the right hand of your father—and then you will remember old friends, eh? What will you do for them then, eh? Eh?”

The evil burning within him was like a flame—dazzling. I had the power to reach out and turn it down low. May God forgive me, I did not. Instead, I said, “I will do this,” and quenched that flame entirely.

He fell to the ground, dead.

Everybody present—and they were among the most powerful men and women in the Empire—saw me do this. When I stalked off to my quarters to brood, not a one of them tried to stop me.

That night, the voices crashed in on me with unprecedented clarity—and all of them were focused exclusively upon me. Some courtiers simply feared my power. Others hoped to corrupt and then blackmail me or by elaborate lies to make me their ally and dupe. To kill me and place the blame on a rival. To convince another to kill me and afterward denounce him. To encourage my ambitions and become my most loyal and trusted lickspittle. In all the castle, there was but one soul whose thoughts were not violent and vicious. Half-maddened by this mental cacophony, and by the guilt I felt for the thoughtless and casual murder of the weapons master, I rose from my bed and dressed.

Then I went to the margrave’s room and knocked upon his door.

As I already knew from his thoughts, he was still awake. The margrave had been sitting with a glass of whiskey, thinking solemnly about suicide. On seeing me, he set aside the glass and said, “A moment ago, dear friend, I was thinking that there remained not one kindly face in all the world—and now, in an act of Providence, you appear to prove me wrong.”

I sank to my knees before the margrave and, taking his hands in mine, cried, “Sir, you must not entertain such evil thoughts as I see in your mind. The world is a dark place, but it would be darker still without your presence. I pray you, do not follow Werther’s path to self-destruction.”

The margrave looked surprised. Then he said, “I keep forgetting what a remarkable young fellow you are. So you can read my thoughts? I should not be surprised. But be comforted. Even that mode of escape is forbidden me. Willingly or not, I must be faithful to your father—and since he desires that I live, so I shall.”

“Then we are returned to our eternal colloquy: Whether or not there is free will and, if there is, why it is denied to the likes of us.”

“It can hardly be called eternal,” the margrave said with a touch of amusement, “for we have only known each other for a month. But, yes, we have had this discussion before.”

Caught in a turmoil of emotions such as would require a Goethe to describe, I blurted out, “Tell me. If you were free from all restraints, what would you do?”

“I would scour this castle with fire and kill all within it,” the Margrave said. “Present company excepted, of course.”

“And if that were denied you? What would be your second choice?”

Without hesitation, the margrave replied, “Oblivion.”

My heart sank. I could see his thoughts and knew that my mentor spoke only the simple truth. Wise though he was, the old man was blind to all possibilities save those he had been brought up to esteem. “Alas,” I said, “I had hoped for a different answer.” But respecting the margrave as I did—and, remember, his was the only moral authority I had ever known—I had, I felt, no choice.

Reaching into his mind, I freed him from my father’s control.

The homunculus lapsed into silence.

After a time, Ritter said, “I’ve heard rumors of what ensued.” Which was a lie, for they had been formal reports. Then, truthfully, “I had no idea my uncle was involved.”

“There were many wizards in my father’s court. So the margrave was, inevitably, as he knew he would be, killed. Not, however, before having his vengeance. For over an hour, he raged up and down the castle corridors. At the time I thought I had done the right thing. Yet it deprived my world of the only being I knew to be worthy of admiration. Even today, I wonder. Does freedom inevitably entail death? Freeing the margrave was the act of a young and inexperienced man. I regret it now.

“I am sorry, Ritter.”

“Don’t be,” Ritter said. “My uncle labored chiefly as a diplomat. But like all the men of my family, he was at heart a soldier. He died a warrior’s death. That is good to hear. What did you do next?”

I fled, with the castle burning behind me. On my way out of the city, I encountered a Swedish merchant returning from Russia with a short wagon train of goods and bought passage with him (or, rather, put the memory of my having paid him in his mind) to Helsinki. He was a fat, ugly, vulgar little man—the first words he ever said to me were, “Pull my finger,” and he roared when I did—yet I found I liked him quite a lot, for he was utterly free of malice. He talked frequently of his wife, whom he sincerely loved, though that did not prevent him from frequenting brothels while he was on the road. Such a specimen was he! So different from the models of my reading.

Old Hannu was a merchant through and through. It was a kind of religion to him. He spoke often of its virtues: “Each man benefits,” he said. “Mark that! I buy lace in Rauma, to the enrichment of those who make it, sell it in St. Petersburg to shopkeepers who immediately double its price, and with the proceeds buy furs from Siberian trappers, who are grateful for my money. Both lace and furs multiply in value through the mere expedient of bringing them elsewhere. Midway between, I buy amber and silver jewelry to be sold in both directions. At every step, I make a profit, as do those I buy from and sell to.

“People speak harshly of merchants because we drive a hard bargain. And it’s true I squeeze the buyers until they shit gold. Yet at the end of the day, everyone goes home satisfied. If there is a magic greater than this, I’m damned if I know of it. Did the Apostle Paul make half so many people happy as I have? Bugger me with a mule if he did.”

When I booked passage with Old Hannu, I had deemed it necessary to pay with fairy gold, for I was penniless and in desperate straits. Traveling with the merchant, however, I came to see that I had cheated this cheerful, awful, self-serving little man as he would never have cheated me. With a shock that was almost physical, I realized that, once again, I had sinned…For which I must atone.

So it was that the next time we came to a city, I accompanied Old Hannu to a tavern where women sold themselves. I did not partake in the pleasures of the flesh, however. Instead, I got into a card game with two professional cheats and a compulsive gambler.

I won everything the three men had. Two of them followed me out onto the street and in the shadows set upon me with cudgels. I could have broken their bodies. Instead, I placed in their minds an awareness of the precariousness of their position: that they were landless men outside the protection of the law, outnumbered and hated by the righteous and yet easy prey to men even more wicked than they. Then I set fire to their cudgels and watched them flee into the outer darkness. Perhaps they reformed their evil ways. If not, I am sure that they practice their illicit trade a great deal more circumspectly than before.

The compulsive gambler I trailed at a distance. He came to a church and, going in, climbed the long spiral stair to the top of the steeple. There, he gripped the stone balustrade with fear-whitened hands, building up his courage to throw himself over. He did not hear me coming up behind him. It gave him a start when I spoke, but that was all to the good. Returning half his money, I said, “You have learned a hard lesson tonight, my friend. Go home and never gamble again.” And I erased the compulsion from his mind.

Thus it went, step by step, for larger and smaller sums. In Lublin, I saved a dowager’s fortune from a venal lawyer and he was fined to pay for my efforts. While stopping at a farmhouse, I uncovered a buried Viking hoard, for which I accepted a modest finder’s fee. Sometimes my actions were legal and other times not. But every one of them ended with the other party better off than before. As Old Hannu would have put it, I gave good weight. And, bit by bit, I paid him back every pin of what I owed him.

Occasionally, men tried to kill me. I made them less murderous and sent them back to their masters.

We came at last, after long and ordinary hardships, to Helsinki. Old Hannu brought me home to meet his family.

Doubtless, you will be nowhere near so dumbstruck as I was to learn that Old Hannu’s wife Leena was in no way the paragon of beauty and virtue he had made her out to be. She was, in her way, as ugly as he. Worse, as I was headed for the outhouse, she ambushed me, rubbing her body against mine in a manner no respectable housewife would. “I’m no beauty,” she said, “and I know it. But lie down with me and close your eyes and you’ll swear I’m as delightful as any of those Russian whores my husband won’t shut up about.” It would have made a dog laugh to see the convolutions I went through to evade her intentions.

Yet for all that, the love Leena and Old Hannu had for each other was genuine. I saw it in their glances, heard it in their speech, witnessed it in their deeds, and of course read it in their thoughts.

Further, they had a daughter.

Kaarina was as pious, virtuous, and chaste as Werther’s beloved Charlotte, and as beauteous as her father imagined her mother to be. I was smitten. When her parents invited me to stay on for a time, I did, just to be near her.

You will scarcely believe this, but Kaarina did not see me as hideous at all. Perhaps this was because her love for animals—she was forever rescuing kittens and fostering crippled dogs—caused her to see me not as a caricature of humanity but simply as one of God’s creatures. For a time, I was content merely being a part of her world, worshipping her from afar.

Then, one day in the garden, Kaarina invited me to sit down beside her. “You are always so silent,” she said. “When you first arrived, I thought you a mute. Tell me something of yourself.”

I needed no urging. All my thoughts, dreams, hopes, fears, loftiest aspirations, and meanest deeds came pouring out of me in a torrent of words. I shared my innermost self as I never had before nor ever would again, save right now with you, holding back only my feelings for Kaarina herself, lest she be alarmed by them. And when I was done…

Kaarina looked at me in blank bewilderment.

“But none of this makes any sense,” she said. “A child born without a mother and grown to man’s estate in a matter of months. A nonpareil who teaches himself to read in an afternoon but kills his instructor on a whim. A redeemer of widows and gamblers who steals from an honest merchant. A master of all magics who has neither wealth nor position. A demigod who can read thoughts but suffers from doing so. How could such a living contradiction even exist? What place could he possibly find for himself in human society? You must clear your head of these dark fantasies and strive to be restored to your true self.”

Kaarina was not angry at me—her character was too refined for that. Nevertheless, her words cut through me like so many knives. I was her physical and intellectual superior and knew it. But our emotions are seated in the body and the body is an animal, even as the bear or the ass. In this regard I am in no way superior to any other man, nor will I ever be, however much my mental powers may increase.

My passion got the better of me.

“But every word I spoke was true!” I cried and, throwing caution to the winds, added, “Furthermore…”

Seeing my distress, Kaarina took my great hand in her wee paws and said, “You may speak your mind freely, my friend. There is nothing you cannot tell me.”

“Then I will say it—I love you.”

May you never see such a look on the face of a woman you esteem! Kaarina’s mouth fell open with astonishment and horror. There could be no mistaking the latter emotion, for I saw it burning in her thoughts like a flare.

I flushed red with humiliation. My blood surged and my hands clenched with the desire to strike Kaarina, to hurt her, to punish her for not loving me. It lasted only a single horrifying instant. Then, overcome with confusion and remorse, I fled. Kaarina, I am sure, prayed for my welfare and the rapid recovery of my wits. As if that would help!

That night, lying abed in the guest room (with the dresser pushed against the door, in case Leena again decided to make an assault upon my virtue), I thought over everything I had gone through and learned since coming to Helsinki. It had just been forcibly demonstrated that there could be no future for Kaarina and me. I needed love, not pity! And she…needed someone she could understand. My feelings for her were undiminished. But, alas, there could be no true communion of thought between us. The imbalance of intellect was simply too great.

It was a painful process working this out while the thoughts of the city roared and crashed over me like a mighty surf. But I came at last to two conclusions. First, that I could not stay in this house a day longer. Second, that in order to adequately think through my life and purpose, I must somehow isolate myself completely from humanity.

In the morning, profusely thanking Old Hannu for his hospitality, I left. Then I set about outfitting an expedition to the unknown Arctic regions. Out of respect for the values of the man I considered the second great mentor of my life, I earned the tremendous sum this required by honest means.

Which was why you almost caught up with me before my ship sailed.

As the ship left the harbor, the eternal pandemonium of thoughts faded and I had to endure only those of the Erebus’s officers and crew. I wept with relief. So you can imagine with what ecstasy I beheld the icy shores of this desolate land. And when the ship sailed off, carrying away with it the last trace of any thought other than my own, I experienced a sensation of pure bliss. Oh, blessed silence! I fell to my knees to thank whatever gods may be for that wondrous gift. Then, carrying all my supplies on my back, I walked inland until I judged myself safe from the influence of any passing ship. There I sat down and proceeded to think. To think, and to plan.

My first conclusion was that I needed a mate—one every bit as beautiful and virtuous as Kaarina but also as intelligent and strong of body as I. There being no such woman, I would have to create her myself. Which would be no easy task. To build such a goddess would require the use of many wizards, the sacrifice of numerous animals and women, and a fortune in related materials. Vast wealth would be required. Further, since such a project could not possibly be kept secret, it would demand defenses: an army, a secure territory with fortified borders, and a system of secret police to protect me from spies and saboteurs. In short, it would entail exactly such an empire as my father is currently endeavoring to create. For a moment, I was aghast at the thought of what atrocities I would have to perform.

Then I resolved to do it. My mate and I would wed and have children who would have children in their turn and their descendants would inevitably supplant the human race. All the world would be theirs and I their Adam.

You blanch, Ritter. Be reassured. My resolution lasted but a moment. For I then reflected that to carry out my plan would be to expose a woman I hoped to love with unswerving dedication to the pain of hearing the thoughts of Mankind which had almost driven me mad. Yes, I could immediately upon her creation put to death all those involved, before her capacity to hear their thoughts came into focus and then carry her off to some desolate tract such as this. But what would happen when she could read my thoughts? When she understood what crimes I had committed in her not-so-immaculate conception?

Logic, alas, told me that the project was doomed to fail.

Thus: No wife, no offspring, no hope, no future.

I had just determined what course of action I should take when I sensed your approach. It occurred to me then that it would be pleasant to share the tale of my life with a sympathetic soul. From what I could sense of your character, it seemed to me that you might well understand my story.

So I let you approach.

For a long time, the homunculus did not speak. Ritter, who was comfortable with silence, waited. At last his host said, “Have you ever considered beetles, Ritter?”

“Beetles,” Ritter said flatly. “No, not since I was a boy.”

“They are, I assure you, fascinating creatures and well worthy of your respect. But they cannot provide much in the way of companionship.” The homunculus stood. “On which note, the time has come to put an end to our colloquy.”

Ritter tried to stand and discovered that he could not. Nor could he move so much as a finger though his lungs, for a mercy, continued to pump air.

The creature looked down on him with an expression of gentle pity. “You are not a good man, Ritter. How could you be, given your occupation? However, you are not as bad a man as you fear you might be—not yet, at any rate.” He went outside, leaving the tent flap open behind him. Over his shoulder, he said, “Imperfect though you are, I wish you well. I wish every single one of you well. But I cannot bear to live among you.”

The homunculus walked steadily away from the tent, toward a distant ridge. When sufficient time had elapsed, he passed over the ridge and out of sight. All the while, Ritter strove in vain to cast off his paralysis. Nor could he enter Freki’s mind—that ability too, it seemed, had been frozen.

Then the sun came up.

There was a tremendous light, at which Ritter discovered himself capable of movement again, for he automatically turned away from it and threw up an arm to protect his eyes. Almost immediately, there followed a sound so thunderous that he clapped his hands over his ears to reduce it to a roar.

Ritter burst from the tent.

Running with all his might, Freki at his heels, he came to the top of the ridge over which the creature had disappeared. Below him Ritter saw a crater half-blasted and half-melted into the ice with a smudge of black at its center, as if a god had reached down from the sky to brush a dirty fingertip against the snow.

When Ritter had done making his report, Sir Toby said, “It is a pity you could not win him over to our cause.”

“In his estimation, our cause was not a good one. I do not believe that the creature saw very much difference between our side and his father’s.”

A darkness congealed within Sir Toby then, as if there were a thunderhead filling his skull and threatening to burst through it with gales and lightning. But he only said, “And who was he to pass judgment on us? The ugly brute!”

“No. He was a handsome man, very much so. By any reasonable definition, he was extremely well made.” Ritter shook his head sadly. “Yet in his own eyes, he was monstrous.”

Buy the Book

The New Prometheus

“The New Prometheus” copyright © 2019 by Michael Swanwick.

Artwork copyright © 2019 by Gregory Manchess.

This series started in kinder days, when the echoes of fascism were confined to fiction. There is something very hopeful about this one; it is much more bearable than the directions the stories were heading some years ago.

Suicide as optimism. Sigh.

And even minor Swanwick is a pleasure — though I’m definitely hoping IDM is a major work.

Immediately bookmarked, thank you so much!

I’m very curious to what degree the last 4 years or so have altered Swanwick’s plan for these stories but 2 in as many months is an unheard of treat.

Two in a few weeks? Wow. This is a great surprise.

I had all but given up on the series. Always a treat to read a new chapter / episode.

Got as far as “A new story in the Mongolian Wizard universe.” and literally said ‘cool’ out loud. I do really enjoy these!

Another fine tale. I love this series!

I LIKE this, thanks

Haha! What a treat! I am over the moon that we’ve gotten TWO stories in such a short time! Now, let this become a trend! :)

Am going to read it as soon as I’ve made my coffee ;)

I love the Frankenstein motif, another great installment, thanks!

A nice twist on the original.

A deeply philosophical reply to Frankenstein. Would that Mary Shelley could read it and reply!

It’s always a pleasure to read a new story in this series.

The ending feels very similar to the Shelley’s original. :)